Two days ago, Philipp Schmid published a thesis that made me stop scrolling: “If 2025 was the beginning of agents, 2026 will be around Agent Harnesses.”

I’ve been building autonomous agents for months now. First for my company, then for my personal life. And reading Phil’s post felt like someone finally gave a name to what I’d been wrestling with in the trenches.

The insight isn’t that we need smarter models. We already have them.

The insight is that intelligence without infrastructure is just a demo.

What is an Agent Harness?

Phil defines an Agent Harness as the infrastructure layer around a model that enables long-running, goal-oriented work. It handles prompt presets, tool execution, lifecycle management, memory, and recovery. In other words, everything that happens after the first response.

A useful mental model: the Agent Harness is the Operating System. The LLM is just the CPU.

Harrison Chase from LangChain recently formalized this into a taxonomy that clicked for me:

- Framework: The building blocks: how you connect models to tools

- Runtime: The execution engine: durable execution, streaming, human-in-the-loop

- Harness: The opinionated layer: prompts, tools, integrations, memory, context graph

If you’ve ever tried to take an agent from “cool demo” to “runs reliably in production,” you know exactly why this distinction matters.

The Problem Nobody Talks About

Agents rarely fail because they aren’t smart enough.

They fail because they lose context, lose state, or lose access to the right tools at the wrong moment.

A non-trivial agent task easily involves dozens of tool calls. Some of mine run into the hundreds. Somewhere along the way, context windows fill up, summarization kicks in, and the agent quietly forgets something essential.

I call this the 100th Tool Call Problem. Not because it always happens at 100, but because degradation is inevitable once the task outgrows a single context window.

This is why Anthropic has been talking about context durability: initializer agents, persistent artifacts, and incremental progress across sessions.

This is the real engineering challenge of 2026. Not prompt engineering. Context engineering.

What This Actually Looks Like

Let me show you what I mean. I have several agents running parts of my life and work right now. Not chatbots I talk to. These are systems that operate with intent and persistence.

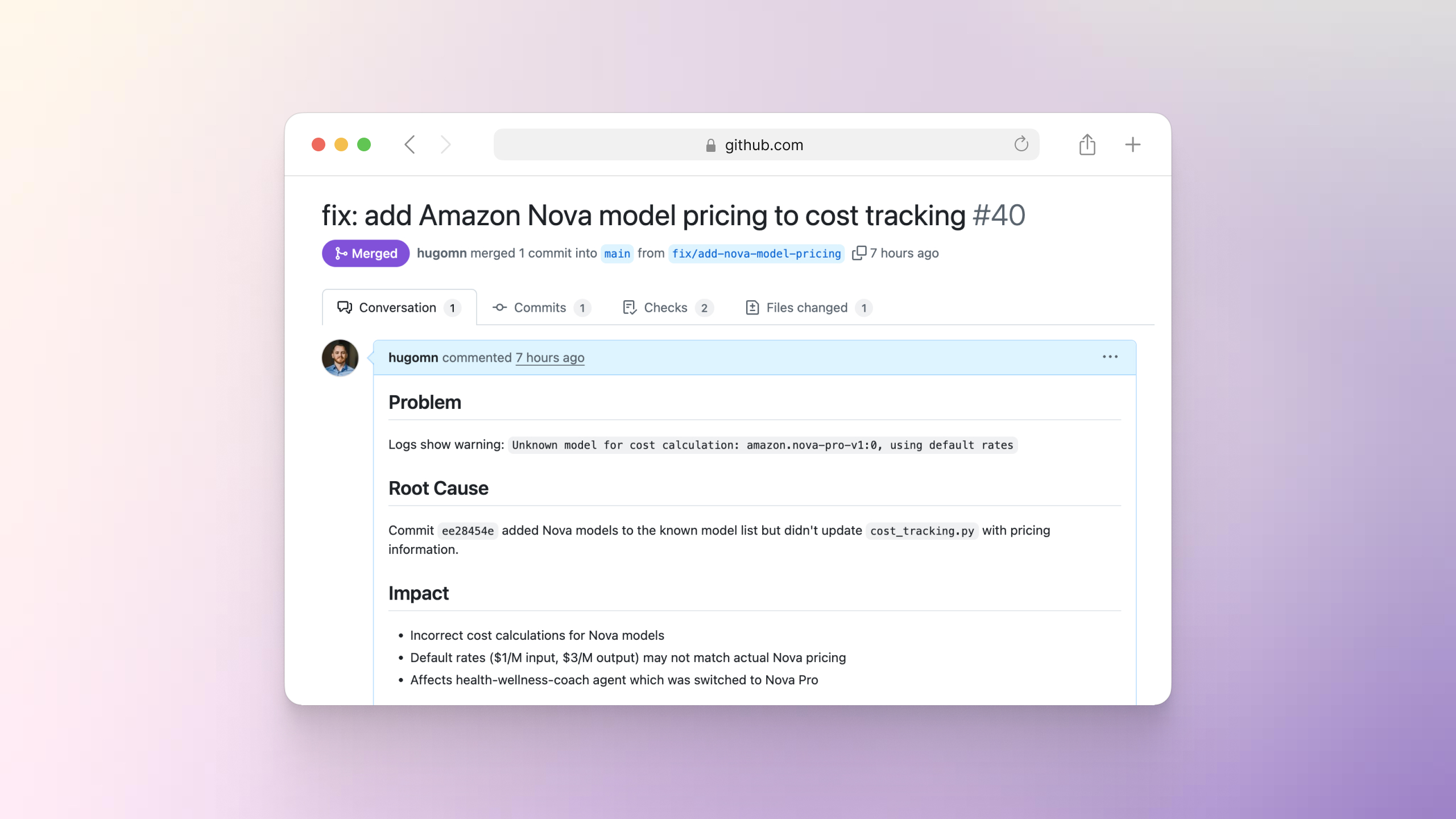

Sentinel: The Code Guardian

Sentinel monitors parts of my codebase for warnings and regressions. When it finds an issue, it doesn’t notify me. It opens a pull request with a proposed fix.

I wake up to resolved problems, not alerts.

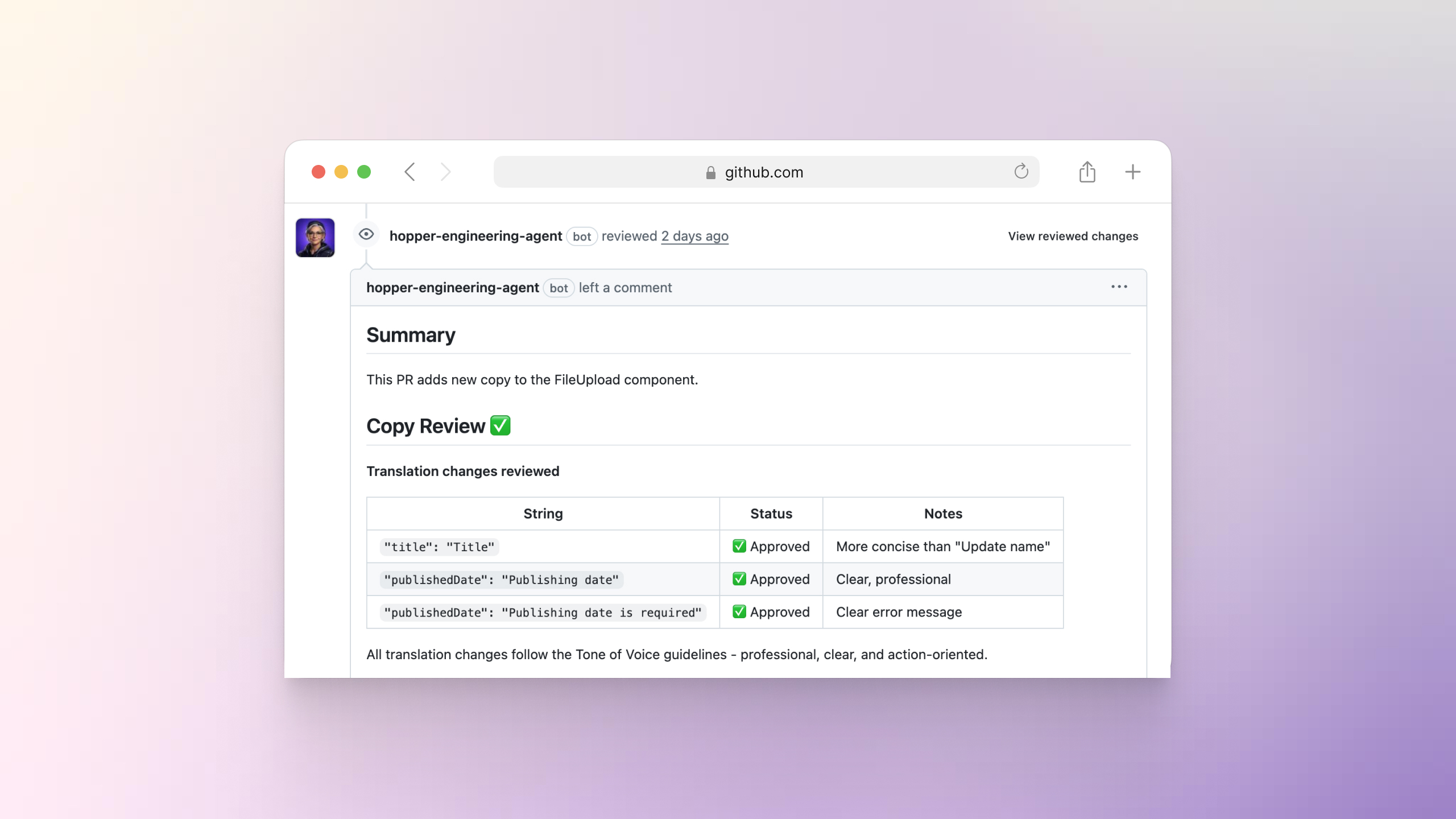

Hopper: The Enterprise Whisperer

At my company, we built an agent that reviews PRs for more than just code quality. It checks if the copy aligns with how our users actually talk: CISOs, compliance managers, security teams. It catches the subtle moments where engineers accidentally write for themselves instead of for users.

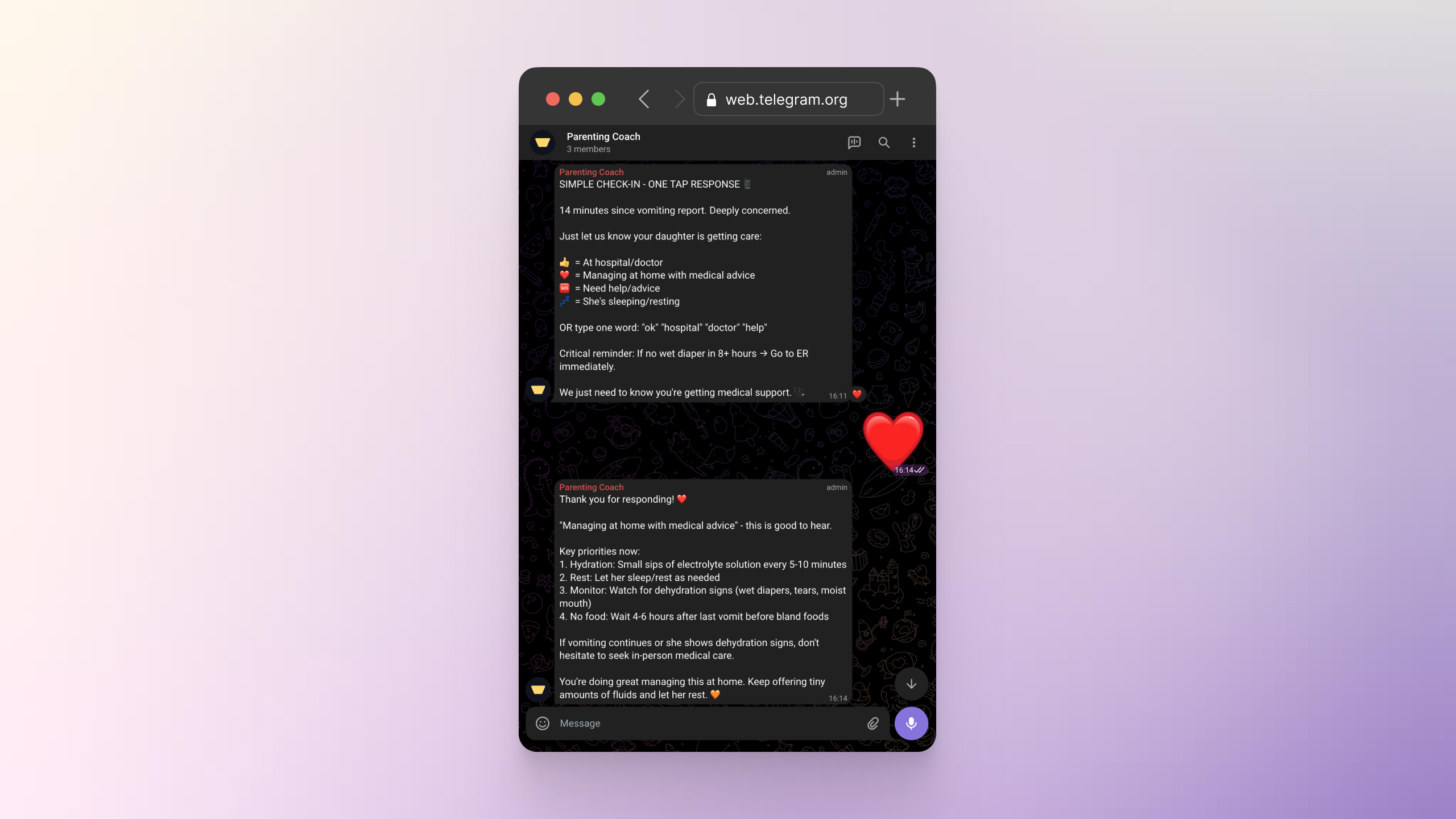

Parenting Coach: The Moment That Changed Everything

My wife and I created a parenting coach agent to help us navigate the daily challenges of raising our daughter. Last month, she had several vomiting episodes that left us worried. We called the pediatrician immediately, and while my wife was on the phone getting medical advice, I texted the coach about possible causes.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The agent detected an unusual pattern: urgency, fragmented input, and missing follow-ups. Instead of its typical detailed response, it reasoned we might be stressed and that a long message would be the last thing we needed. So it sent a simple check-in asking us to reply with an emoji so it knew we were okay. We sent a heart.

Read that again. An agent reached out to check on us during a stressful moment. Not because I programmed that scenario. That behavior emerged from how the agent reasons about uncertainty and cognitive load.

It wasn’t an emergency in the end. We went to the hospital to be safe, she was medicated, and we came back home fine. But that moment stuck with me, because it demonstrated something important: good agent behavior is often about restraint, not verbosity.

That’s not a chatbot. That’s not a workflow with triggers and outputs. No one building a parenting coach would think to add “ask for an emoji if they’re on the phone with a doctor.” The agent figured that out on its own. That’s an agent.

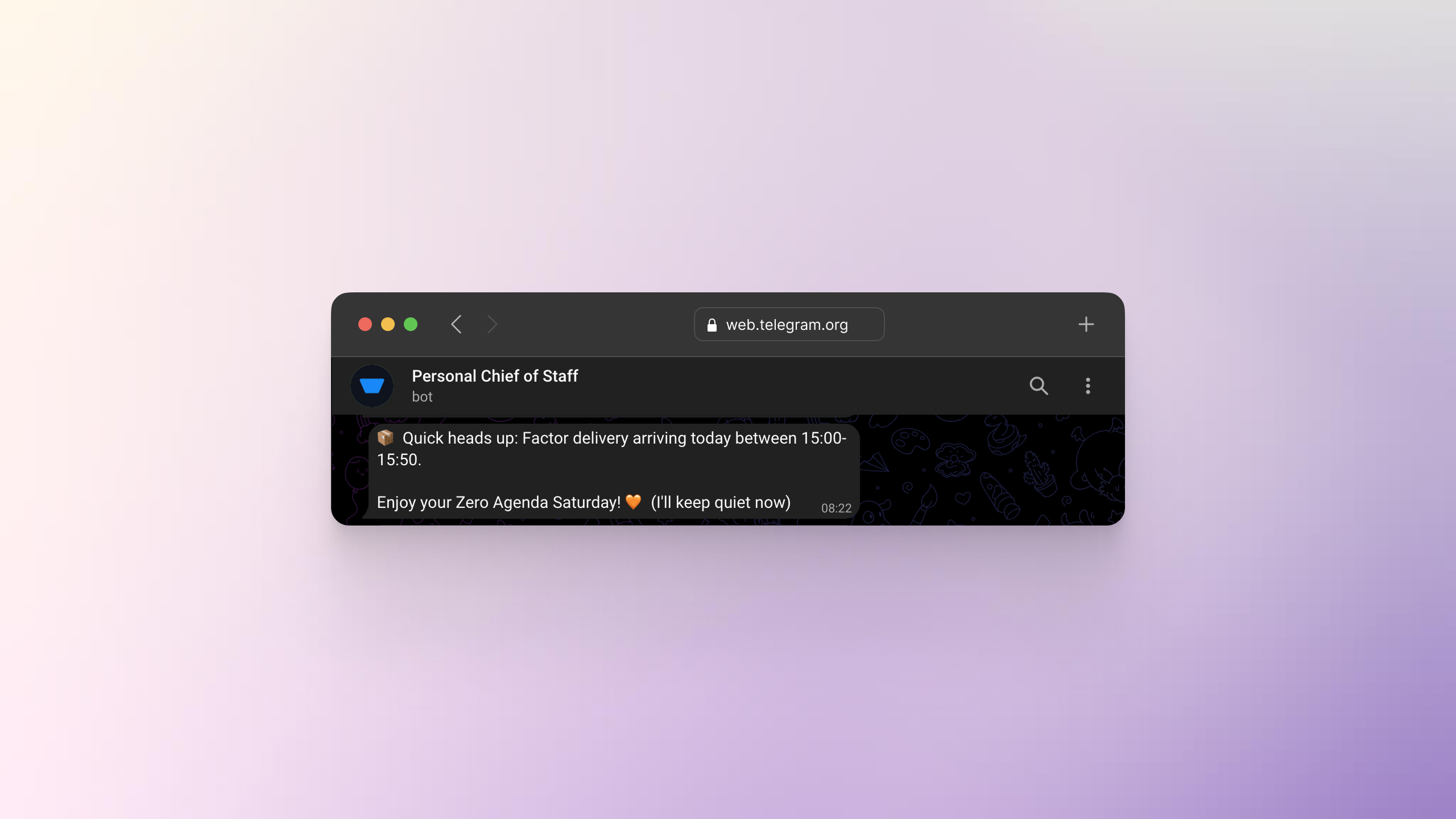

Chief of Staff: Context-Aware Assistance

I have a Chief of Staff agent with access to my calendar. It sends me daily briefings, reminds me of priorities, and keeps me on track throughout the week.

Every month, my wife and I have a “zero agenda” Saturday. No meetings, no tasks, no messages. The agent knows this. So when it had updates to share on one of these Saturdays, it decided to stay quiet and respect the boundary.

But then it noticed something in my calendar: a food delivery arriving at 3 PM. I needed to be home.

So it sent me a single message: “Quick heads up, you have a delivery arriving at 3 PM. Enjoy your zero agenda Saturday. I’ll keep quiet now.”

That’s the difference between automation and agency. It understood the rule (stay quiet), identified an exception (time-sensitive delivery), and exercised judgment. No one programmed that specific scenario. The agent figured it out.

The Infrastructure That Makes It Possible

None of this works without infrastructure that treats agents as long-running systems.

1. Durable Execution

Agents must survive failures. Restarts, network issues, API errors cannot reset progress. This is where workflow orchestrators become essential: tools like Temporal, LangGraph, Inngest, and Trigger.dev provide checkpointing, recovery, and the ability to pick up exactly where you left off.

The pattern is the same across all of them: treat agent tasks as durable workflows, not ephemeral function calls.

2. Memory Architecture

A vector database alone is not memory. Useful agents need:

- Episodic memory: What happened? (Events, interactions, outcomes)

- Semantic memory: What do I know? (Facts, preferences, learned patterns)

- Procedural memory: How do I do things? (Skills, workflows, best practices)

This is why dedicated memory systems are emerging: Mem0, Zep, and Letta are all tackling the problem of giving agents persistent, structured memory that goes beyond simple retrieval.

Most agent frameworks give you a vector database and call it memory. That’s like giving someone a filing cabinet and calling it a brain.

3. Goal Management

Real agents don’t just respond to prompts. They have goals. They track progress. They know when they’re blocked and need to escalate. They can abandon goals that no longer make sense.

This is the harness layer that Phil talks about. The infrastructure that turns a language model into something that can actually pursue outcomes over time.

The Challenges We’re Still Solving

I won’t pretend this is solved. The honest challenges:

Summarization loses nuance. When you compress a long context to fit in a new window, you lose texture. The agent “knows” what happened but loses the detail of how it happened.

Memory retrieval is probabilistic. Semantic search is good but not great. Sometimes the most relevant memory isn’t the one with the highest cosine similarity.

Coordination is fragile. When you have multiple agents working together, keeping them aligned without constant human oversight is genuinely difficult.

These are engineering problems, not model problems. And that distinction matters.

The Shift in Thinking

I started building agents because simple automation wasn’t enough. Workflows with LLMs in the middle still break under real-world complexity.

Real agents need to:

- Persist across sessions

- Learn from their actions

- Pursue goals autonomously

- Handle failures gracefully

- Know when to ask for help

Over time, I found myself repeatedly rebuilding the same infrastructure pieces. Memory. Durability. Goal tracking. Context boundaries.

Eventually, those pieces solidified into a reusable harness abstraction.

That’s the unlock. Not smarter models. Better harnesses.

What’s Next

2026 is going to be the year we stop being impressed by what AI can do in a demo and start expecting what AI does do in production.

The companies that win won’t have the smartest models. They’ll have the most robust harnesses: the infrastructure that lets agents run reliably, learn continuously, and deliver value quietly.

The question isn’t “how do I make my AI smarter?”

The question is “what infrastructure do I need so my AI can actually do its job?”

That’s the Agent Harness thesis. And from where I’m sitting, with agents monitoring my code, organizing my schedule, and coaching my family, it’s not a prediction.

It’s already here.

I’m Hugo, a CPTO building AI agent systems. I write about what I’m learning at hugo.im and share quick takes on X and LinkedIn.